The first long-term research project on Sichuan

With Elena Valussi (Loyola University Chicago) I have started the very first long-term research project on Sichuan religions, shifting the attention from the usual urban centre and the Jiangnan region to the Southwest, and finally bringing the periphery to the centre of the academic attention.

Within this team project, I have continued my research on female communities and their making of the Buddhist history, and Buddhist education. Other studies have concerned travelling monks, and the spatial ecology of religious diversity.

(In)visible Nuns and Nunneries: Female Hidden History of Sichuan Buddhism

During my very first trip to Chengdu I started a long-term research on a small nunnery, the Jinsha Nunnery金沙庵, via archival research and interviews to the resident nuns. The nunnery is built on a tiny and busy commercial alley, with the main gate quite hidden by surrounding shops. Jinsha is a small community, but it is also a temple that was built in the Qing dynasty, and whose history includes the succession of more than thirteen generations of nuns, which is a rare and remarkable achievement in the female history of Buddhism.

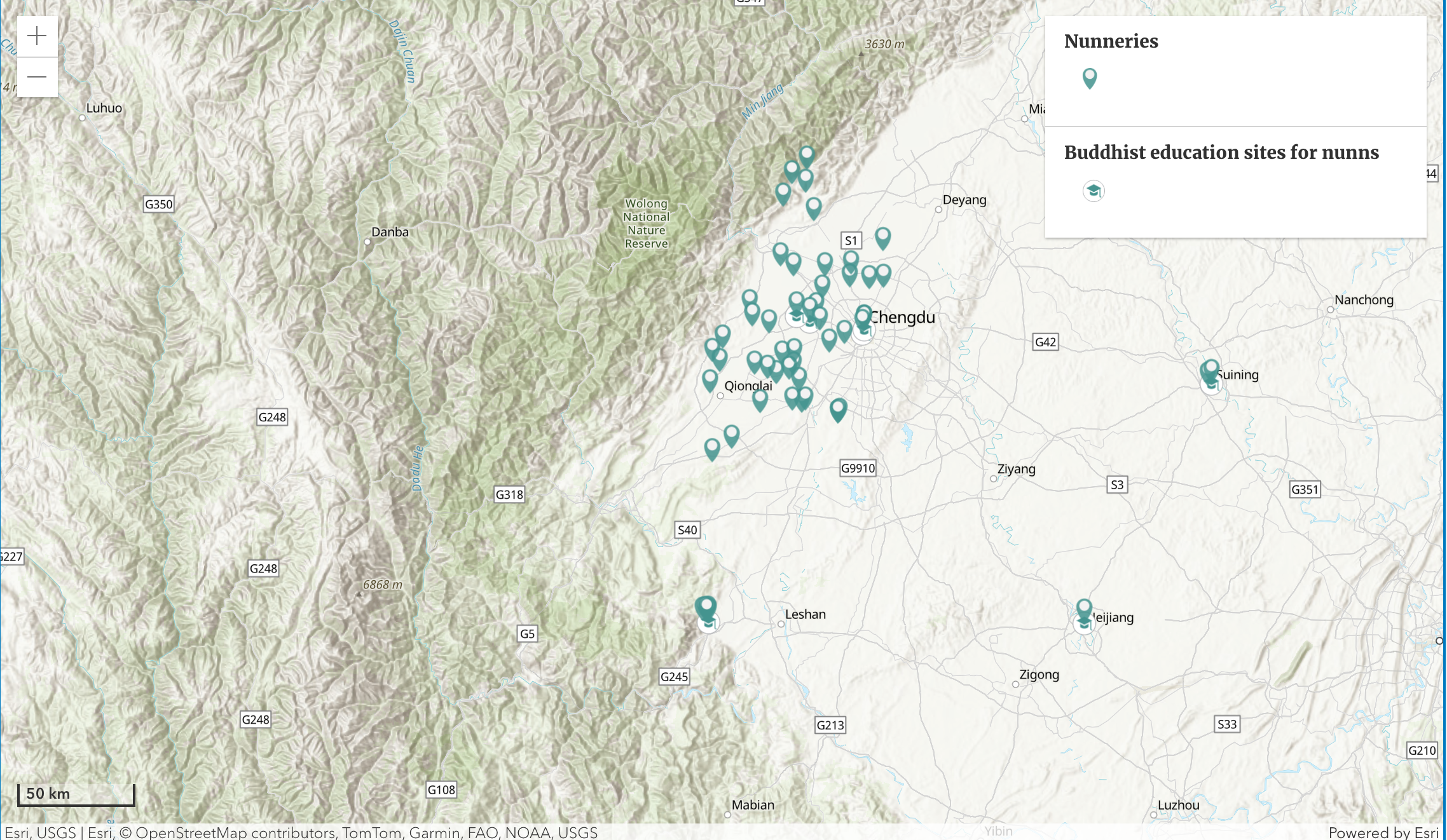

I have extended my research to, so far, a total of more than 60 nunneries, located in various districts, counties, and cities within Chengdu, and other areas like Suining, Leshan, Mt. Emei, Neijiang, Nanchong. More sites will be added in 2024.

Several of these nunneries display photos of previous abbesses and resident nuns, and also of other monastics who have been important in the histories of these sites, in small rooms and shrines; these ‘pagoda’ are not merely a memorial of the temple nuns, but they represent the collective memory of larger communities, which go beyond the borders of a single site, and show how temples and networks can intersect and develop in a micro-area.

Preliminary findings have been presented in several talks and later published. Among the articles, “Monk Changyuan 昌圓 (1879–1945), Nuns in Chengdu, and Revaluation of Local Heritage: Voicing Local (In)Visible Narratives of Modern Sichuan Buddhism” (Journal of Chinese Religions 49, no. 2: 191-239), addresses nuns and nunneries in Chengdu, with special reference to their schools and other education initiatives. “Buddhist Discourses in Modern Suining (Sichuan): Local Discourses within Chinese and Regional Narratives” (Asia Major 34, no. 2: 127-179) also analyzes nuns and nunneries in Suining from the late Qing up to today. And the piece in Chinese “汉传佛教多元化图景中边缘女性的经验:近现代四川比丘尼的隐形和显性” (西南民族大學學報, no.3: 50-56), which has been highly praised by Chinese scholars; this pieces summarises my argument on (in)visibility of nuns in Republican Sichuan, under the main headings of charisma and leadership, education accomplishments, contribution in the Sino-Japanese war, memorialisation strategies.

You can also see a digital map, with the sites that I have visited so far and details of Buddhist women leaders in their communities. While the majority of sites are temples, some others are schools created for improving nuns’ education. A brief overview of the history of the sites and their conditions today is integrated with names of resident nuns and images; the map is developed and maintained by Yuwei Zhou.

The Chinese Way of Diversity: Communities and Spatial Ecology

Average Chinese with religious inclinations visit temples of different denominations with equal devotion and build multi-faith in-home shrines; a strong sense of belonging and membership to specific traditions is mostly replaced with a pragmatic conception of an open system of beliefs in continuous exchange and recreation, and situation-based worship. On the other hand, the Chinese state, in premodern and modern times, have created clear distinctions, institutionally and legally, among denominations; this fixed official chart excludes hybrid practices, local and popular beliefs; and first and foremost, it does not reflect the fluidity and co-existence registered within local communities.

Diversity in the Chinese world is then twofold: a) the official political differentiation, the normative narrative, where ‘diversity’ is a concept applied on the governmental level, in the past and present, to create artificial distinctions that otherwise are less experienced or visible (normative-artificial diversity); b) the experiential story of diversity, the empirical narrative, where we can detect a diversity of processes and synergies among beliefs and practices in the production of heterogenous identities (empirical-actual diversity).

My interest lies in the ’empirical-actual diversity’, with special attention to language, communities rituals, and sites. Sichuan has been a great case study giving not only the richness of ethnic and cultural denominations, but also and especially the diversity of processes and synergies among beliefs and practices in the production of heterogenous identities. Sites like the 川王宮 in 大邑, and places that have witnessed transition in labels like 璧山寺 are sample case-studies in my work.

Traveling Monks: Searching for the Buddha in the late Qing

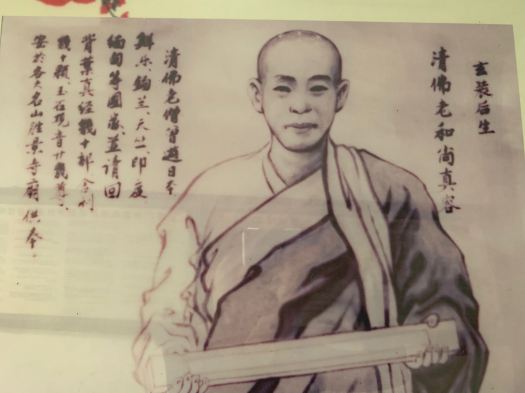

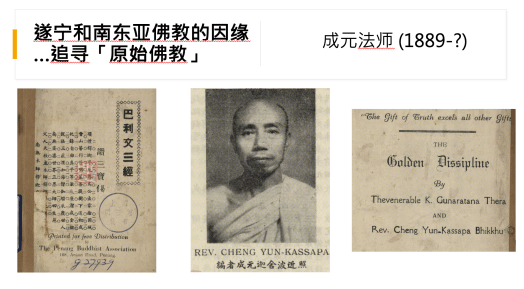

Suining 遂宁 is well-known for a wide-spread devotion to Guanyin 觀音信仰, and the development of local practices and stories about Princess Miaoshan 妙善. Besides collecting material on nuns from the late Qing and Republican time, I also gathered unpublished sources of key monks in the Republican period like Qingfu 清福 (1862-1940) and Changnian 長念 (1908-1990).

Qingfu, and other monks from Suining like Chengyuan 成元, could be seen as leading figures in the revival of attention towards early Indian Buddhism and the Theravāda tradition.

My study concentrates on life and practice of the monk Qingfu, and his travels to South and Southeast Asia. Qingfu brought Buddha statues, relics and sutras back to China, this is why he has been titled a “modern-day Xuanzang”. Part of my research concentrates on Qingfu’s travelogue《源因略記》, and has reconstructed his travel routes and visits via a digital map.

Sangha Education and Local Buddhism in Republican Sichuan and Chongqing

I have unpacked important ‘Sangha education networks’ centred on the figures of local monks like Shengqin 聖欽 (1869-1964), 遍能 (1906-1997), 昌圓 (1879-1945), and the lay intellectual Wang Enyang 王恩洋 (1897-1964). As for the latter, I have also researched an important cross-province Sichuan-Nanjing network centred on him and his lecturing career.

The monk Changyuan 昌圓 (1879-1945) was crucial in the Republican period for his role in developing Buddhist education for nuns in Chengdu, and his overall position in Republican Sichuan Buddhism. The monk Bianneng 遍能 (1906-1997) is another key case study in my research, as he was born in the end of the Qing dynasty and lived through the first Republican period, the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the Cultural Revolution, and the beginning of the new opening to religion post-1980. Bianneng is the leading figure of a ‘diachronic network’ and crossed several Buddhist centres during his career. Active in many Buddhist areas like Mt. Emei, Leshan, Chengdu, and Chongqing, he is considered the most important figure in Sichuan for the modern development of Sangha education. Wang Enyang 王恩洋 was another educator, involved in several structures of learning, and active between Sichuan and Nanjing. The Dongfang Cultural and Religious Institute 東方文教研究院, located at Shengshui Monastery 聖水寺, in Neijiang, was one of these schools. The Fawang Institute of Buddhist Studies 法王寺佛學院, located at Fawang Monastery 法王寺, in Luzhou 蘆洲, was an important education centre for the Sangha in the final years of the Republican era, and had monks like the well-known Yinshun 印順 (1906-2005). I have presented research results in invited lectures, and included some data in my publication on nuns. Articles on other education leaders will be out in 2024.